Since I began documenting shamanism on Jeju Island, more and more attention has begun to be paid to these traditional healers, especially with the increase in tourism to the island. Even so, it is certainly not evident that the tradition of shamanism on Jeju Island will continue in its traditional form. There are young shamans on the island, but their numbers are few. Telling is the fact that the dangwol—an aging population—are quickly decreasing in number. Gentrification, too, is diversifying the local population. While thousands of new-comers to the island capitalize off of native symbolism in their various tourist operations, legitimate interest in preserving the culture is mostly hard to assess. The profusion of commercial development has lead to the destruction of many shamanic sites and other cultural assets.

In this series, I offer a photographic profile of a number of shimbang I have spent time with over the years. Included are some video interviews, footage of village rituals and a short documentary. Some of the material is excerpted from my film Spirits: The Story of Jeju Island’s Shamanic Shrines.

The shimbang, Sun Shil Seo, reading rice grains, a divination method

The shimbang with her village's dangwol (adherents of Jeju Island shamanism)

The yo-ryoung, a bell used during shamanic rites

Shrine-goers place offerings on the shrine altar

Village residents stand before their shrine's altar

Fruit and rice-cake offerings

Shrine ceremonies are a community affair. There is much laughter.

Two shrine-goers warm up by a fire.

Standing before the gods

Bowing before the altar

Shaman Sun Shil Seo enjoys a moment to joke around after a busy morning

The shaman, Sun Shil Seo, discusses the difference between shamanic healing and western medicine in this short video. On Jeju Island, shamanic ceremonies today serve healing functions which are seen as complimentary to western medicinal practices. Seminars have been held in local hospitals to educate medical professionals on the role shamanic practice plays, for instance, in helping resolve the effects of trauma.

The shaman, Young Chul Kim

Young Chul Kim performs an uplifting shamanic song emphasizing the idea of ushering in good fate.

The traditional shimbang responsible for Waheul Village's bonhyang shrine takes a moment to rest. Offerings adorn the grandfather god's altar behind her.

Performing the climax of the annual lunar January shrine rite.

A shrine-goer ties an offering to the grandmother goddess's tree. On Jeju Island, gods often appear as couples. In Waheul, the Grandfather and Grandmother are feted at separate altars.

The village leader of Waheul voices his stance on maintaining the shrine in its natural state. Developers and local politicians from the city often lobby to turn the shrine into a tourist destination. In recent years, they have even made an appearance at shrine rites. Adding parking lots and other facilities would be badly seen by the community as it would disrupt the sanctity of the area. The village, like many on the island, is facing environmental battles already. In Waheul's case, a concrete factory threatens to cause significant air quality issues.

Mother and daughter visit the shrine

A child peers into his grandmother's offering basket.

A team of shamans from around Jeju Island gather under the shrine's holy trees to perform divination. This will last all morning before the performative part of the ritual begins. Village residents light small fires to warm themselves around the periphery of the shrine.

The shaman, Stone Mountain Kim, and her flock

Shaman Kim

Shimbang Kim councils the village leader as according to the advice she has received from the Grandfather and Grandmother gods of the shrine. The community's power structure is inverted in this moment; the shaman and gods take on significant authority.

Taking on the role of the hunter god named for the island's central peak--Halla Mountain, Kim takes up bamboo wands, representing weapons of the hunt. This grandfather god enters her body and takes control of her movements.

Driving out taboo from the shrine and village. Taboo, as in many Eurasian polytheistic traditions, is a central concept.

Village residents wait in line to receive divination from the shaman.

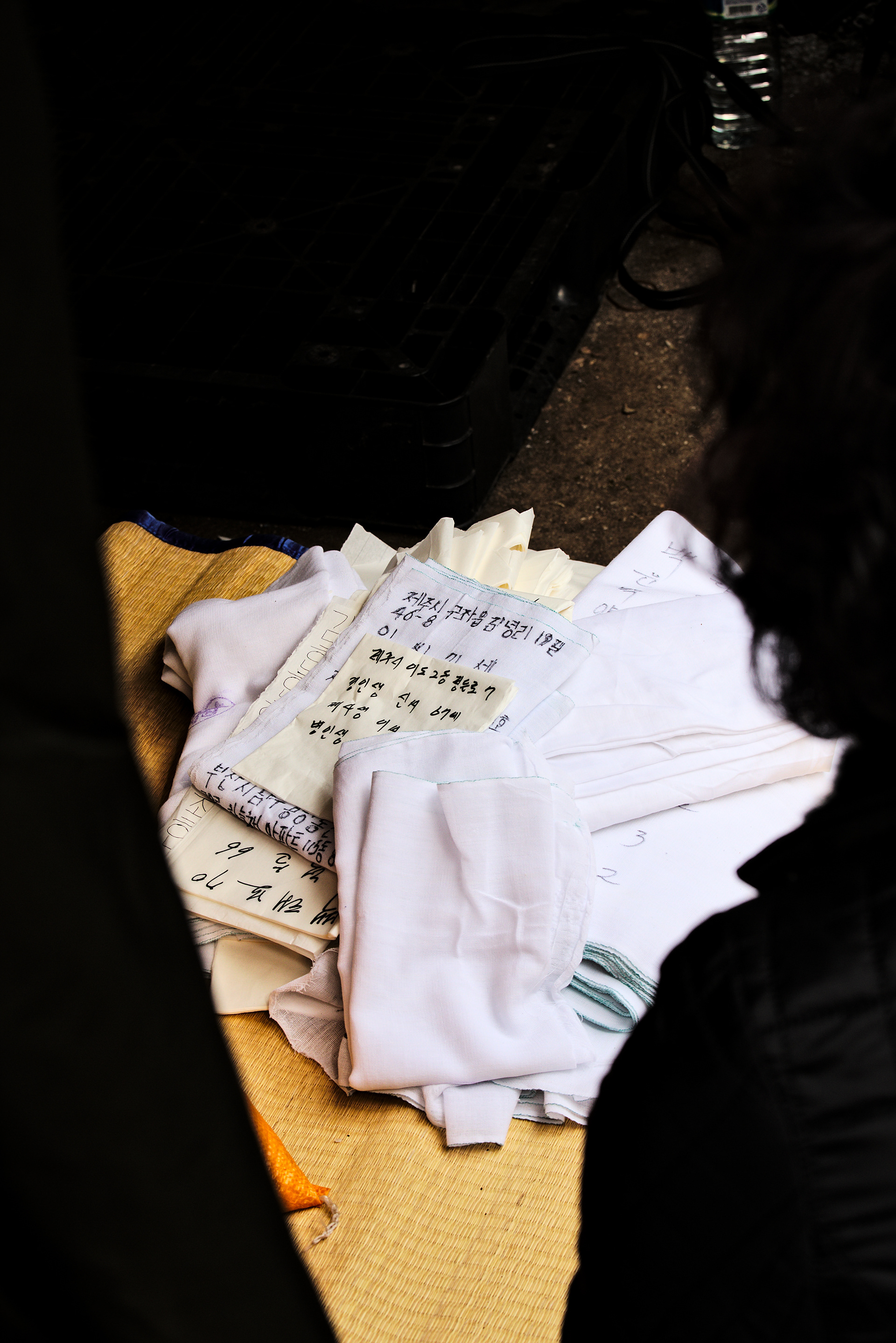

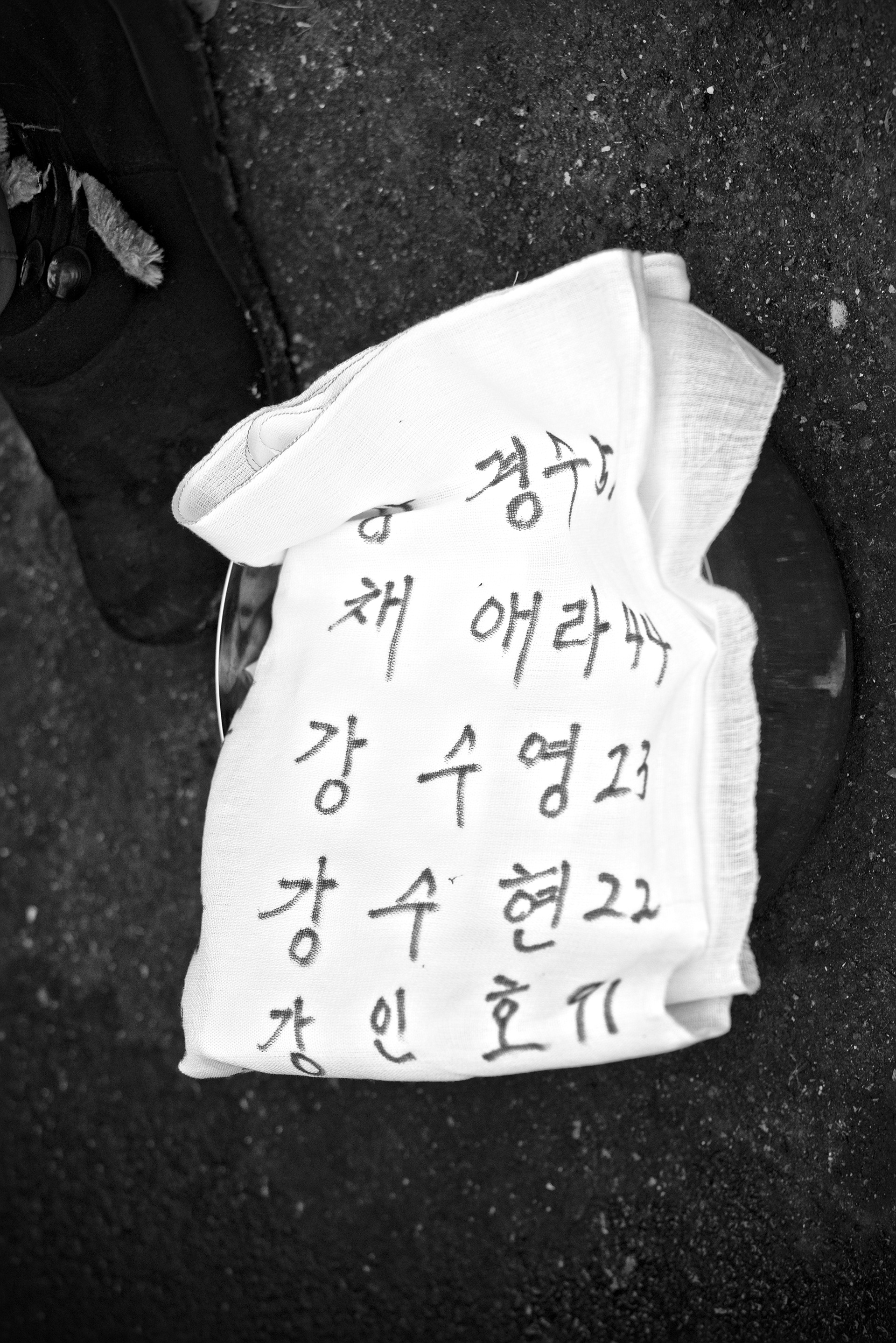

Residents write down details about their family members and other information which the shaman communicates to the gods.

A resident clarifies a detail of the notes she's made for the shaman.

Shaman Kim with a village resident

The shaman, Bok Ja Go, during preparations for the annual ceremony welcoming the Youngdeung Gods to the island.

Dancing with shamanic tools, the gods' knives used for performing psychic healing, and ringing the yoryoung bell

Village residents arrive at the shrine carrying their offerings

Women in communities on Jeju Island are particularly close to the shimbang. The shimbang, like priests of other faiths, are bound to secrecy when it comes to the private matters.

Bok Ja Go and her flock

Laying offerings before the altar

Cloth offerings

A woman observes her mother-in-law arranging ritual offerings on the altar. She will be soon take on the responsibility.

A female abalone diver arrives to the shrine ceremony

Recording shamanic myths with Bok Ja Go. Photo courtesy of Tanner Jones.

Senior shaman, In Suk Oh, addresses members of her community

Giving advice and prescriptions to village residents with the aid of divination coins

Performing shrine myths.

Divination with spirit knives

The shaman In-suk Oh adjusting her drum

Performing the shrine myths. Three generations of shamanic instruments--spirit knives and bells--are in place on the altar in the foreground.

Tossing the keunpyoung out of the shrine is synonymous with driving taboo from the village.

A young shimbang performs a ceremony dedicated to the Youngdeung gods